THE END of this story was first brought to my attention when Fromwiller returned from his trip to Mount Kemmel, with a very strange tale indeed and one extremely hard to believe.

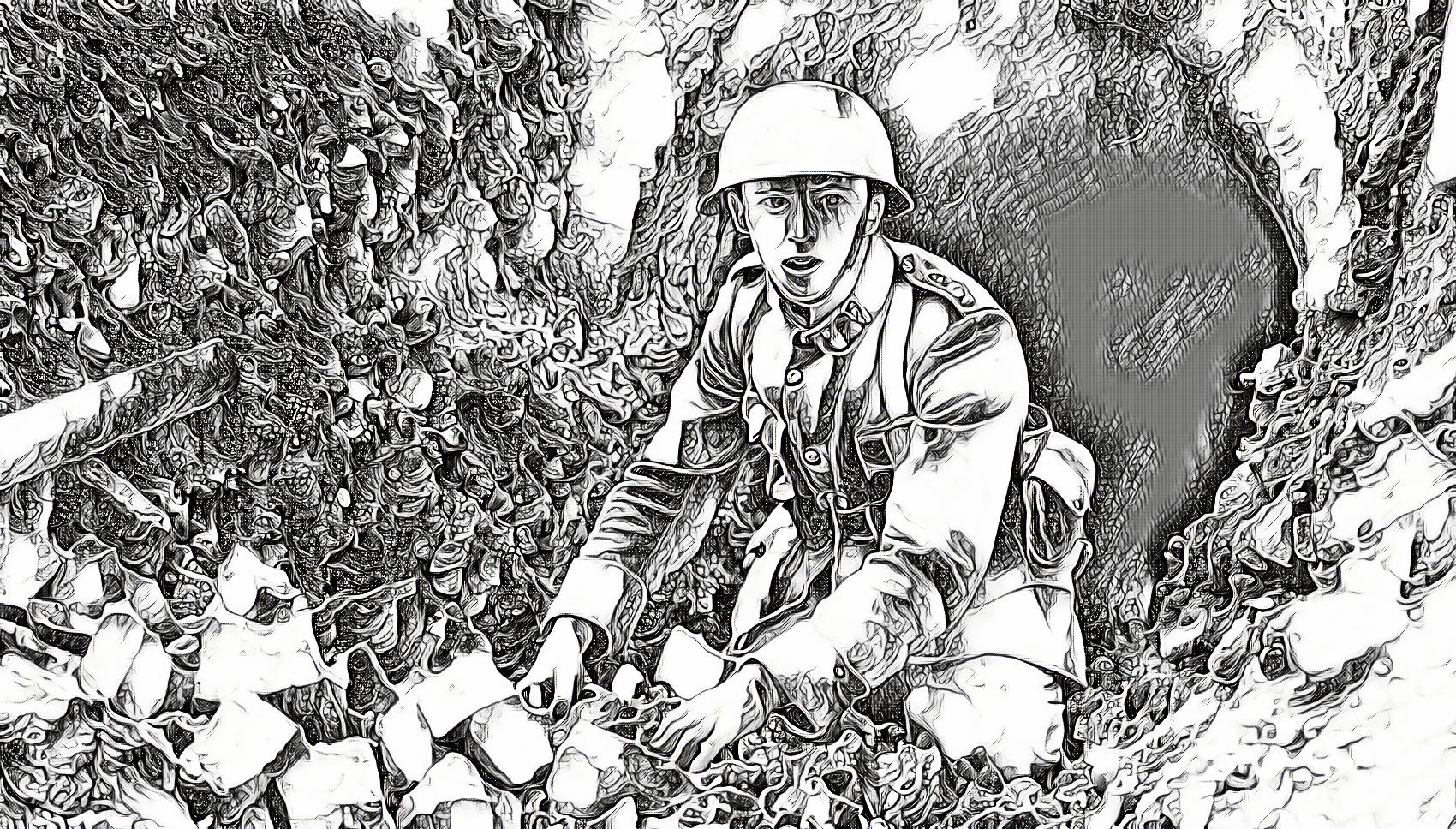

But I believed it enough to go back to the Mount with “From” to see if we could discover anything more. And after digging for awhile at the place where “From’s” story began, we made our way into an old dugout that had been caved in, or at least where all the entrances had been filled with dirt, and there we found, written on German correspondence paper, a terrible story.

We found the story on Christmas day, 1918, while making the trip in the colonel’s machine from Watou, in Flanders, where our regiment was stationed. Of course, you have heard of Mount Kemmel in Flanders: more than once it figured in newspaper reports as it changed hands during some of the fiercest fighting of the war. And when the Germans were finally driven from this point of vantage, in October, 1918, a retreat was started which did not end until it became a race to see who could get into Germany first.

The advance was so fast that the victorious British and French forces had no time to bury their dead, and, terrible as it may seem to those who have not seen it, in December of that year one could see the rotting corpses of the unburied dead scattered here and there over the top of Mount Kemmel. It was a place of ghastly sights and sickening odors. And it was there that we found this tale.

With the chaplain’s help, we translated the story, which follows:

“FOR two weeks I have been buried alive! For two weeks I have not seen daylight, nor heard the sound of another person’s voice. Unless I can find something to do, besides this everlasting digging, I shall go mad. So I shall write. As long as my candles last, I will pass part of the time each day in setting down on paper my experiences.

“Not that I need to do this in order to remember them. God knows that when I get out the first thing I shall do will be to try to forget them! But if I should not get out!…

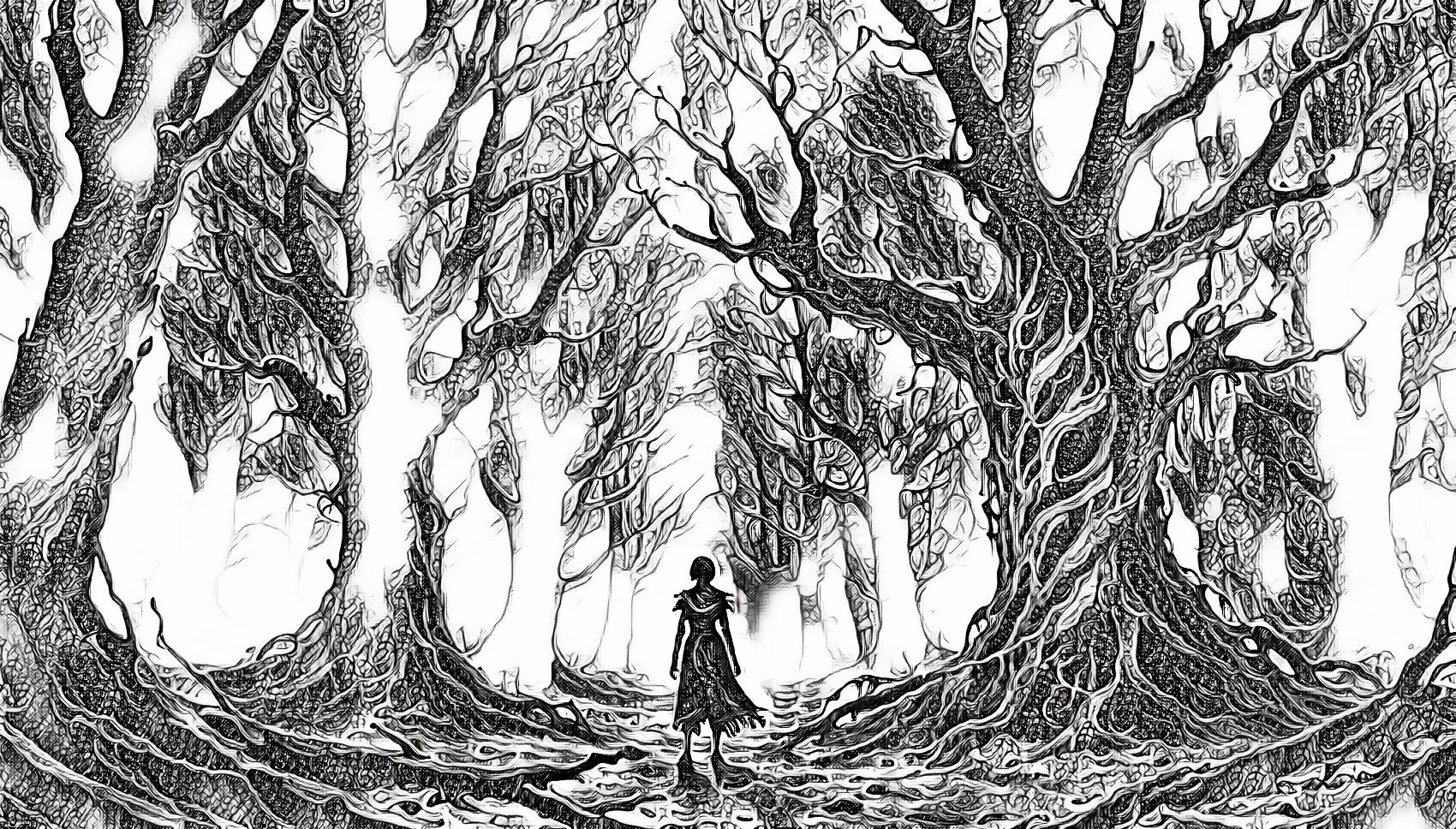

“I am an Ober-lieutenant in the Imperial German Army. Two weeks ago my regiment was holding Mount Kemmel in Flanders. We were surrounded on three sides and subjected to a terrific artillery fire, but on account of the commanding position we were ordered to hold the Mount to the last man. Our engineers, however, had made things very comfortable. Numerous deep dugouts had been constructed, and in them we were comparatively safe from shell-fire.

“Many of these had been connected by passageways so that there was a regular little underground city, and the majority of the garrison never left the protection of the dugouts. But even under these conditions our casualties were heavy. Lookouts had to be maintained above ground, and once in a while a direct hit by one of the huge railway guns would even destroy some of the dugouts.

[48]

“A little over two weeks ago—I can’t be sure, because I have lost track of the exact number of days—the usual shelling was increased a hundred fold. With about twenty others, I was sleeping in one of the shallower dugouts. The tremendous increase in shelling awakened me with a start, and my first impulse was to go at once into a deeper dugout, which was connected to the one I was in by an underground passageway.

“It was a smaller dugout, built a few feet lower than the one I was in. It had been used as a sort of a storeroom and no one was supposed to sleep there. But it seemed safer to me, and, alone, I crept into it. A thousand times since I have wished I had taken another man with me. But my chances for doing it were soon gone.

“I had hardly entered the smaller dugout when there was a tremendous explosion behind me. The ground shook as if a mine had exploded below us. Whether that was indeed the case, or whether some extra large caliber explosive shell had struck the dugout behind me, I never knew.

“After the shock of the explosion had passed I went back to the passageway. When about half-way along it, I found the timbers above had fallen, allowing the earth to settle, and my way was effectually blocked.

“So I returned to the dugout and waited alone through several hours of terrific shelling. The only other entrance to the dugout I was in was the main entrance from the trench above, and all those who had been above ground had gone into dugouts long before this. So I could not expect anyone to enter while the shelling continued; and when it ceased there would surely be an attack.

“As I did not want to be killed by a grenade thrown down the entrance; I remained awake in order to rush out at the first signs of cessation of the bombardment and join what comrades there might be left on the hill.

“After about six hours of the heavy bombardment, all sound above ground seemed to cease. Five minutes went by, then ten; surely the attack was coming. I rushed to the stairway leading out to the air. I took a couple of strides up the stairs. There was a blinding flash and a deafening explosion.

“I felt myself falling. Then darkness swallowed everything.”

“HOW long I lay unconscious in the dugout I never knew.

“But after what seemed like a long time, I practically grew conscious of a dull ache in my left arm. I could not move it. I opened my eyes and found only darkness. I felt pain and a stiffness all over my body.

“Slowly I rose, struck a match, found a candle and lit it and looked at my watch. It had stopped. I did not know how long I had remained there unconscious. All noise of bombardment had ceased. I stood and listened for some time, but could hear no sound of any kind.

“My gaze fell on the stairway entrance. I started in alarm. The end of the dugout, where the entrance was, was half filled with dirt.

“I went over and looked closer. The entrance was completely filled with dirt at the bottom, and no light of any kind could be seen from above. I went to the passageway to the other dugout, although I remembered it had caved in. I examined the fallen timbers closely. Between two of them I could feel a slight movement of air. Here was an opening to the outside world.

“I tried to move the timbers, as well as I could with one arm, only to precipitate a small avalanche of dirt which filled the crack. Quickly I dug at the dirt until again I could feel the movement of air. This might be the only place where I could obtain fresh air.

“I was convinced that it would take some little work to open up either of the passageways, and I began to feel hungry. Luckily, there was a good supply of canned foods and hard bread, for the officers had kept their rations stored in this dugout. I also found a keg of water and about a dozen bottles of wine, which I discovered to be very good. After I had relieved my appetite and finished one of the bottles of wine, I[49] felt sleepy and, although my left arm pained me considerably, I soon dropped off to sleep.

“The time I have allowed myself for writing is up, so I will stop for today. After I have performed my daily task of digging tomorrow, I shall again write. Already my mind feels easier. Surely help will come soon. At any rate, within two more weeks I shall have liberated myself. Already I am half way up the stairs. And my rations will last that long. I have divided them so they will.”

“YESTERDAY I did not feel like writing after I finished my digging. My arm pained me considerably. I guess I used it too much.

“But today I was more careful with it, and it feels better. And I am worried again. Twice today big piles of earth caved in, where the timbers above were loose, and each time as much dirt fell into the passageway as I can remove in a day. Two days more before I can count on getting out by myself.

“The rations will have to be stretched out some more. The daily amount is already pretty small. But I shall go on with my account.

“From the time I became conscious I started my watch, and since then I have kept track of the days. On the second day I took stock of the food, water, wood, matches, candles, etc., and found a plentiful supply for two weeks at least. At that time I did not look forward to a stay of more than a few days in my prison.

“Either the enemy or ourselves will occupy the hill I told myself, because it is such an important position. And whoever now holds the hill will be compelled to dig in deeply in order to hold it.

“So to my mind it was only a matter of a few days until either the entrance or the passageway would be cleared, and my only doubts were as to whether it would be friends or enemies that would discover me. My arm felt better, although I could not use it much, and so I spent the day in reading an old newspaper which I found among the food supplies, and in waiting for help to come. What fool I was! If I had only worked from the start, I would be just that many days nearer deliverance.

“On the third day I was annoyed by water, which began dripping from the roof and seeping in at the sides of the dugout. I cursed that muddy water, then, as I have often cursed such dugout nuisances before, but it may be that I shall yet bless that water and it shall save my life.

“But it certainly made things uncomfortable; so I spent the day in moving my bunk, food and water supplies, candles, etc., up into the passageway. For a space of about ten feet it was unobstructed, and, being slightly higher than the dugout, was dryer and more comfortable. Besides, the air was much better here, as I had found that practically all my supply of fresh air came in through the crack between the timbers, and I thought maybe the rats wouldn’t bother me so much at night. Again I spent the balance of the day simply in waiting for help.

“It was not until well into the fourth day that I really began to feel uneasy. It suddenly became impressed on my consciousness that I had not heard the sound of a gun, or felt the earth shake from the force of a concussion, since the fatal shell that had filled the entrance. What was the meaning of the silence? Why did I hear no sounds of fighting? It was as still as the grave.

“What a horrible death to die! Buried Alive! A panic of fear swept over me. But my will and reason reasserted itself. In time, I should be able to dig myself out by my own efforts. It would take time but it could be done.

“So, although I could not use my left arm as yet, I spent the rest of that day and all of the two following days in digging dirt from the entrance and carrying it back into the far corner of the dugout.

“On the seventh day after regaining consciousness I was tired and stiff from my unwanted exertions of the three previous days. I could see by this time that it was a matter of weeks—two or three, at least—before I could hope to[50] liberate myself. I might be rescued at an earlier date, but, without outside aid, it would take probably three more weeks of labor before I could dig my way out.

“Already dirt had caved in from the top, where the timbers had sprung apart, and I could repair the damage to the roof of the stairway only in a crude way with one arm. But my left arm was much better. With a day’s rest, I would be able to use it pretty well. Besides, I must conserve my energy. So I spent the seventh day in rest and prayer for my speedy release from a living grave.

“I also reapportioned my food on the basis of three more weeks. It made the daily portions pretty small, especially as the digging was strenuous work. There was a large supply of candles, so that I had plenty of light for my work. But the supply of water bothered me. Almost half of the small keg was gone in the first week. I decided to drink only once a day.

“The following six days were all days of feverish labor, light eating and even lighter drinking. But, despite all my efforts, only a quarter of the keg was left at the end of two weeks. And the horror of the situation grew on me. My imagination would not be quiet. I would picture to myself the agonies to come, when I would have even less food and water than at present. My mind would run on and on—to death by starvation—to the finding of my emaciated body by those who would eventually open up the dugout—even to their attempts to reconstruct the story of my end.

“And, adding to my physical discomfort, were the swarming vermin infesting the dugout and my person. A month had gone by since I had had a bath, and I could not now spare a drop of water even to wash my face. The rats had become so bold that I had to leave a candle burning all night in order to protect myself in my sleep.

“Partly to relieve my mind, I started to write this tale of my experiences. It did act as a relief at first, but now, as I read it over, the growing terror of this awful place grips me. I would cease writing, but some impulse urges me to write each day.”

“THREE weeks have passed since I was buried in this living tomb.

“Today I drank the last drop of water in the keg. There is a pool of stagnant water on the dugout floor—dirty, slimy and alive with vermin—always standing there, fed by drippings from the roof. As yet I cannot bring myself to touch it.

“Today I divided up my food supply for another week. God knows the portions were already small enough! But there have been so many cave-ins recently that I can never finish clearing the entrance in another week.

“Sometimes I feel that I shall never clear it. But I must! I can never bear to die here. I must will myself to escape, and I shall escape!

“Did not the captain often say that the will to win was half the victory? I shall rest no more. Every waking hour must be spent in removing the treacherous dirt.

“Even my writing must cease.”

“OH, GOD! I am afraid, afraid!

“I must write to relieve my mind. Last night I went to sleep at nine by my watch. At twelve I woke to find myself in the dark, frantically digging with my bare hands at the hard sides of the dugout. After some trouble I found a candle and lit it.

“The whole dugout was upset. My food supplies were lying in the mud. The box of candles had been spilled. My finger nails were broken and bloody from clawing at the ground.

“The realization dawned upon me that I had been out of my head. And then came the fear—dark, raging fear—fear of insanity. I have been drinking the stagnant water from the floor for days. I do not know how many.

“I have only about one meal left, but I must save it.”

“IHAD a meal today. For three days I have been without food.

“But today I caught one of the rats that infest the place. He was a big[51] one, too. Gave me a bad bite, but I killed him. I feel lots better today. Have had some bad dreams lately, but they don’t bother me now.

“That rat was tough, though. Think I’ll finish this digging and go back to my regiment in a day or two.”

“HEAVEN have mercy! I must be out of my head half the time now.

“I have absolutely no recollection of having written that last entry. And I feel feverish and weak.

“If I had my strength, I think I could finish clearing the entrance in a day or two. But I can only work a short time at a stretch.

“I am beginning to give up hope.”

“WILD spells come on me oftener now. I awake tired out from exertions, which I cannot remember.

“Bones of rats, picked clean, are scattered about, yet I do not remember eating them. In my lucid moments I don’t seem to be able to catch them, for they are too wary and I am too weak.

“I get some relief by chewing the candles, but I dare not eat them all. I am afraid of the dark, I am afraid of the rats, but worst of all is the hideous fear of myself.

“My mind is breaking down. I must escape soon, or I will be little better than a wild animal. Oh, God, send help! I am going mad!”

“Terror, desperation, despair—is this the end?”

“FOR a long time I have been resting.

“I have had a brilliant idea. Rest brings back strength. The longer a person rests the stronger they should get. I have been resting a long time now. Weeks or months, I don’t know which. So I must be very strong. I feel strong. My fever has left me. So listen! There is only a little dirt left in the entrance way. I am going out and crawl through it. Just like a mole. Right out into the sunlight. I feel much stronger than a mole. So this is the end of my little tale. A sad tale, but one with a happy ending. Sunlight! A very happy ending.”

AND that was the end of the manuscript. There only remains to tell Fromwiller’s tale.

At first, I didn’t believe it. But now I do. I put it down, though, just as Fromwiller told it to me, and you can take it or leave it as you choose.

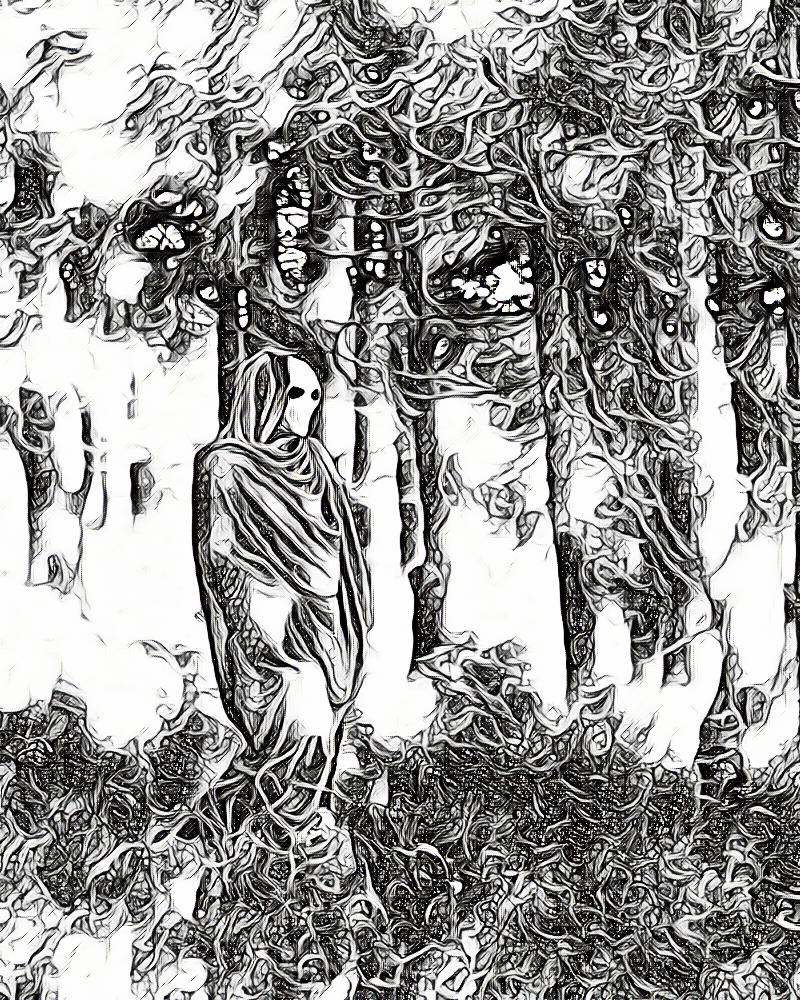

“Soon after we were billeted at Watou,” said Fromwiller, “I decided to go out and see Mount Kemmel. I had heard that things were rather gruesome out there, but I was really not prepared for the conditions that I found. I had seen unburied dead around Roulers and in the Argonne, but it had been almost two months since the fighting on Mount Kemmel and there were still many unburied dead. But there was another thing that I had never seen, and that was the buried living!

“As I came up to the highest point of the Mount, I was attracted by a movement of loose dirt on the edge of a huge shell hole. The dirt seemed to be falling in to a common center, as if the dirt below was being removed. As I watched, suddenly I was horrified to see a long, skinny human arm emerge from the ground.

“It disappeared, drawing back some of the earth with it. There was a movement of dirt over a larger area, and the arm reappeared, together with a man’s head and shoulders. He pulled himself up out of the very ground, as it seemed, shook the dirt from his body like a huge, gaunt dog, and stood erect. I never want to see such another creature!

“Hardly a strip of clothing was visible, and, what little there was, was so torn and dirty that it was impossible to tell what kind it had been. The skin was drawn tightly over the bones, and there was a vacant stare in the protruding eyes. It looked like a corpse that had lain in the grave a long time.

“This apparition looked directly at me, and yet did not appear to see me. He looked as if the light bothered him. I spoke, and a look of fear came over his face. He seemed filled with terror.

[52]

“I stepped toward him, shaking loose a piece of barbed wire which had caught in my puttees. Quick as a flash, he turned and started to run from me.

“For a second I was too astonished to move. Then I started to follow him. In a straight line he ran, looking neither to the right or left. Directly ahead of him was a deep and wide trench. He was running straight toward it. Suddenly it dawned on me that he did not see it.

“I called out, but it seemed to terrify him all the more, and with one last lunge he stepped into the trench and fell. I heard his body strike the other side of the trench and fell with a splash into the water at the bottom.

“I followed and looked down into the trench. There he lay, with his head bent back in such a position that I was sure his neck was broken. He was half in and half out of the water, and as I looked at him I could scarcely believe what I had seen. Surely he looked as if he had been dead as long as some of the other corpses, scattered over the hillside. I turned and left him as he was.

“Buried while living, I left him unburied when dead.”